- Home

- Anderson, Poul

The Avatar

The Avatar Read online

I

I was a birch tree, white slenderness in the middle of a meadow, but had no name for what I was. My leaves drank of the sunlight that streamed through them and set their green aglow, my leaves danced in the wind, which made a harp of my branches, but I did not see or hear. Waning days turned me brittle golden, frost stripped me bare, snow blew about me during my long drowse, then Orion hunted his quarry beyond this heaven and the sun swung north to blaze me awake, but none of this did I sense.

And yet I marked it all, for I lived. Each cell within me felt in a secret way how the sky first shone aloud and afterward grew quiet, air gusted or whooped or lay dreaming, rain flung chill and laughter, water and worms did their work for my reaching roots, nestlings piped where I sheltered them and soughed, grass and dandelions enfolded me in richness, the earth stirred as the Earth turned among stars. Each year that departed left a ring in me for remembrance. Though I was not aware, I was still in Creation and of it; thought I did not understand, I knew. I was Tree.

II

When Emissary passed through the gate and Phoebus again shone upon her, half of the dozen crew folk who survived were gathered in her common room, together with the passenger from Beta. After their long time away, they wanted to witness this return on the biggest view screens they had and share a ceremony, raising goblets of the last wine aboard to the hope of a good homecoming. Those on duty added voices over the intercom. "Salud. Proost. Skol. Banzai. Sa de. Zdoroviye. Prosit. Mazel tov. Sante. Viva. Aloha" each spoke of a very special place.

From her post at the linkage computer, Joelle Ky whispered, on behalf of those who had stayed behind forever, "Zivio" for Alexander Vlantis, "Kan bei" for Yuan Chichao, "Cheers" for Christine Burns. She added nothing of her own, thought what a sentimental old fool she was, and trusted that nobody had heard. Her gaze drifted to a small screen supposed to provide her with visual data should any be needed. Amidst the meters, controls, input and output equipment which crowded the cabin, it seemed like a window on the world.

"World," though, meant "universe." Amplification was set at one, revealing simply what the naked eye would have seen. Yet stars shone so many and bright, unyielding diamond, sapphire, topaz, ruby, that the blackness around and beyond was but a chalice for them. Even in the Solar System, Joelle could have picked no constellations out of such a throng. However, the shape of the Milky Way was little changed from nights above North America. With that chill brilliance for a guide, she found an elvenglow which was M3, and it had looked the same at Beta, too, for it is sister to our whole galaxy.

Nonetheless she suddenly wanted a more familiar sight. The need for the comfort it would give surprised her. She, the holothete, to whom everything visible was merely a veil that reality wore. The past eight Earth-years must have drunk deeper of her than she knew. Unwilling to wait the hours, maybe days until she could see Sol again, she ran fingers across the keyboard before her, directing the scanner to bring in Phoebus. At least she had glimpsed it when outbound, and countless pictures of it throughout her life.

The helmet was already on her head, the linkage to computer, memory bank, and ship's instruments already complete. The instant after she desired that particular celestial location, she had calculated it. To her the operation felt everyday: felt like knowing where to move her hand to pick up a tool or knowing which way a sound was coming from. There was nothing numinous about it.

The scene switched to a different sector. A disc appeared, slightly larger than Sol observed from Earth or Luna, a trifle yellower, type G5. Photospheric luminance, ten percent above what Earth got, had been automatically stopped down to avoid blinding her. Lesser splendors remained undimmed. Thus she made out spots on the surface, flares along the limb, nacre of corona, slim wings of zodiacal light. Yes, she thought, Phoebus has the same kind of beauty as my sun. Centrum does not, and only now do I feel how lonely was that lack.

Her touch ranged onward, calling for a sight of Demeter. This problem her unaided brain could have solved. Having newly made transit, Emissary floated near the gate; and it held a Lagrange 4 position with respect to the planet, in the same orbit though sixty degrees ahead. The scanner must merely course along the ecliptic to find what she wished.

At a distance of 0.81 astronomical units, unmagnified, Demeter resembled the stars about it, stronger than most and bluer than any. Are you still yonder, Dan Brodersen? Joelle wondered, and then, oh, yes, you must be. I've been gone for eight years, but a bare few of your months have passed.

How many, exactly? I don't know. Fidelio isn't quite sure.

Captain Langendijk's general announcement interrupted her reverie. "Attention, please. We've registered two vessels on our radars. One is obviously the official watchcraft, and is signalling for tight-beam communication. I'll put that over the intercom, but kindly do not interrupt the talk, or make any unnecessary noise. Best they don't know you are listening."

For a moment Joelle was puzzled. Why should he take precautions, as if Emissary's return might not be the occasion for mankind-wide rejoicing? What put the note of strain into his tone? The answer struck inward. She had been indifferent to partisan matters, they scarcely existed for her, but once recruited into this crew, she couldn't help hearing talk of strife and intrigue. Brodersen had rather grimly explained the facts to her, and they had often been a subject of conversation at Beta. A considerable coalition within humanity had never wanted the expedition and would not be happy at its success.

Two vessels, both presumably in orbit around the T machine. The second must be Dan's.

"Thomas Archer, commanding World Union watchship Faraday, speaking," said a man's voice. His Spanish was accented like hers. "Identify yourself."

"Willem Langendijk, commanding exploratory ship Emissary Spanish Emisario," replied her captain. "We're passing through on our way back to the Solar System. May we commence maneuvers?"

"What- but-" Archer obviously struggled with amazement. "Well, you do seem like- But everybody expected you'd be gone for years!"

"We were."

"No. I witnessed your transit. That was, uh, five months ago, no more."

"Ah-ha. Give me the present date and time, please."

"But- you-"

"If you please." Joelle could well imagine how Langendijk's lean face tautened to match his sternness.

Archer blurted the figures off a chronometer. She summoned from the memory bank the exact clock reading when she and her fellows had finished tracing out the guidepath here and twisted through space-time to their unknown goal. Subtraction yielded an interval of twenty weeks and three days. She could as readily have told how many seconds, or microseconds, had passed out of Archer's lifespan, but he had only given information to the nearest minute.

"Thank you," Langendijk said. "For us, approximately eight Terrestrial years have passed. It turns out that the T machine is indeed a time machine of sorts, as well as a space transporter. The Betans -the beings whom we followed-calculated our course to bring us out near the date when we left."

Silence hummed. Joelle noticed she was aware of her environment with more than usual intensity. Free falling, the ship kept her weightless in a loosened safety harness. The sensation was pleasant, recalling flying dreams of long ago when she was young. (Afterward her dreams had changed with her mind and soul, as she grew into being a holothete.) Air from a ventilator murmured and stroked her cheeks. It bore a slight greenwood odor of recycling chemicals and, at its present stage of the variability necessary for health, coolness and a subliminal pungency of ions. Her heart knocked loud in her ears. And, yes, twinges in her left wrist had turned into a steady ache, she was overdue for an arthritis booster, time went, time went. Probably the Others themselves could not change that.

"Well," Archer said in En

glish. "Well, I'll be God damned. Uh, welcome back. How are you?"

Langendijk switched to the same language, in which he felt a touch more at ease and which was in fact used aboard Emissary about as often as Spanish. "We lost three people. But otherwise, Captain, believe me, the news we bear is all wonderful. Besides being anxious to get home-you will understand that-we can hardly wait to spread our story through the Union."

"Did you-" Archer paused, as if half afraid to utter the rest. Quite possibly he was. Joelle heard him draw breath before he plunged: "Did you find the Others?"

"No. What we did find was an advanced civilization, nonhuman but friendly, in contact with scores of inhabited worlds. They're eager to establish close relations with us, too; they offer what my crew and I think are some fantastically good deals. No, they know nothing more about the Others than we do, except for the additional gates they've learned how to use. But we, the next several generations of man will have as much as we can do to assimilate what the Betans will give.

"Now I'm sorry, Captain, I realize you'd love to hear everything, but that would take days, and anyhow, we have orders not to linger. The Council of the World Union commissioned us and requires we report first to it. That is reasonable, no? Accordingly, we request clearance to proceed straight on to the Solar System."

Again Archer was mute a while. Was something more than surprise at work in him? On impulse, Joelle called on the ship's exoinstrumental circuits. An immediate inrush of data lured her. It wasn't a full perception, but still, as far as possible, how easy and how blessed to comprehend yonder cosmos as a whole and become one with it! Resisting, she concentrated solely on radar and navigational information. In a split pulsebeat, she calculated how to bring Faraday onto her viewscreen.

There was no particular reason for that. She knew what the watchcraft looked like: a tapered gray cylinder so as to be capable of planetfall, missile launcher and ray projector recessed into the sleekness-wholly foreign to the huge, equipment-bristling, fragile sphere which was Emissary. When the picture changed, she didn't magnify and amplify to make the vessel visible across a thousand kilometers. Instead, the sight of two dully glowing globes, red and green, coming into the scanner field, against the stars, snatched at her. Those were markers around the T machine. The Others had placed them. Her augmented senses told her that a third likewise happened to be visible on the receiver; it was colored ultraviolet.

Vaguely she heard Archer: "-quarantine?" and Langendijk: `Well, if they insist, but we walked on Beta, again and again for eight years, and we have a Betan native with us, and nobody's caught any diseases. Pinski and de Carvalho, our biologists, studied the subject and tell me cross-infection is impossible. Biochemistries are too unlike."

Caught up in the beacons, she quite stopped listening. Oh, surely someday, she, holothete, could speak mind to mind with their makers, if ever she found them.

Though what would they make of her, perhaps in more than one meaning of the phrase? Even physical appearance might conceivably not be altogether irrelevant to them. It was an odd thing to do in these circumstances, but for the first time in almost a decade Joelle Ky briefly considered her body as flesh, not machinery.

At fifty-eight Earth-years of age, her hundred and seventy-five centimeters remained slim, verging on gaunt, her skin clear and pale and only lightly lined. In that and the high cheekbones her genes kept a bit of the history, which her name also remembered. She had been born in North America, in what was left of the old United States before it federated with Canada. Her features were delicate, her eyes large and dark. Hair once sable, bobbed immediately below the ears, was the hue of iron. Clad now in the working uniform of the ship, a coverall with abundant pockets and snaploops, she seldom wore anything very much more stylish at home.

A smile flickered. How silly can I get? If one thing is certain about the Others, it is that none of them will come courting me! Could it be the thought of Dan, yonder on Demeter? Additional nonsense. Why, at Beta I became eight years his senior.

Somehow that raised Eric Stranathan for her, the first and last man with whom she fell wholly in love. Across a quarter century-plus the time she had been gone on this mission-he came back, seated opposite her in a canoe on Lake Louise, among mountains, in piney air, under a night sky nearly as vast as what lay around Emissary; and staring upward, she whispered, "How do the Others see that? What is it to them?"

`What are they?" he answered. "Animals evolved beyond us; machines that think; angels dwelling by the throne of God; beings, or a being, of a kind we've never imagined and never can; or what? Humans have been wondering for more than a hundred years now."

She mustered pride. "We'll come to know."

"Though holothetics?" he asked.

"Maybe. Else through-who can tell? But I do believe we will. I have to believe that."

"We might not want to. I've got an idea we'd never be the same again, and that price might be too high."

She shivered. "You mean we'd forsake all we have here?"

"And all we are. Yes, it's possible." His dear lanky form stirred, rocking the boat. "And I wouldn't, myself. I'm so happy where I am, this moment."

That was the night they became lovers.

Joelle shook herself. Stop. Be sensible. I'm obsessive about the Others, I know. Seeing their handiwork again serving not aliens but humans must have uncapped a wellspring in me. But Willem's right. The Betans should be enough for many generations of my race. Do the Others know that? Did they foresee it?

She was faintly shocked to note that her attention had drifted from the intercom for minutes. She wasn't given to introspection or daydreaming. Maybe it had happened because she was computer-linked. At such times, an operator became a greater mathematician and logician, by orders of magnitude, than had ever lived on Earth before the conjunction was developed. But the operator remained a mortal, full of mortal foolishness. I suppose my habit of close concentration while I'm in this state took over in me. Since I'm not used to dealing with emotions, the habit got out of hand.

She knew peripherally that an argument had been going on. Hearkening, she heard Archer state: "Very well, Captain Langendijk, nobody foresaw you'd return this early-if ever, to be frank-and therefore I don't have specific orders regarding you. But my superiors did brief me and issue a general directive."

"Ah?" replied the skipper of Emissary. "And what does that say?"

"Well, uh, well, certain highly placed people worry about more than your bringing a strange bug to Earth. The idea is, they don't know what you might bring back. Look, I'm not saying a monster has taken over your ship and is pretending to be you, anything paranoid like that."

"I should hope not! As a matter of fact, sir, the Betans -the name we gave them, of course -the Betans are not just friendly, they are anxious to know us well. That is why they will trade with us on terms that would else be unbelievably favorable. They stand to gain even more."

Wariness responded: "What?"

"It would take long to explain. There is something vital they hope to learn from us."

It twisted in Joelle, something that I have never yet really learned myself, nor ever likely will.

Archer's voice jarred the thought out of her. "Well, maybe. Though I think that reinforces the point, that nobody can tell what the effect might be. . . on us. And the World Union is none too stable, you know. You plan to report straight to the Council-"

"Yes," Langendijk said. "We'll proceed to the neighborhood of Earth, call Lima, and request instructions. What's wrong with that?"

"Too public!" Archer exclaimed. After a few seconds: "Look, I'm not at liberty to say much. But. . . the officials I mentioned want to, uh, debrief you in strict privacy, examine your materials, that sort of thing, before they issue any news release. Do you see?"

"M-m-m, I had my suspicions," Langendijk rumbled. "Go on."

"Well, under the circumstances, et cetera, I'm going to interpret my orders as follows. We'll accompany you through the gate, to th

e Solar System. Radio interlock of our autopilots, of course, to make sure the ships come out at the other end simultaneously. You'll have no communication with anybody but us, on a tight beam-we'll handle everything outside-until you hear differently. Is that clear?"

"Rather too clear."

"Please, Captain, no offense intended, nothing like that. You must understand what a tremendous business this is. People who, uh, who're responsible for billions of human lives, they're bound to be cautious. Including, for a start, me."

"Yes, I agree you are doing your duty as you see it, Captain Archer. Besides, you have the power." Emissary bore a couple of guns, but almost as an afterthought; her fire control officers doubled as pilots of her launch. Though she could build up huge velocities if given time, her top acceleration with payload and reaction mass on hand was under two gravities; and her gyros or lateral jets could turn her about only ponderously. No one had imagined her as a warcraft, a lone vessel setting off into what might be a whole galaxy. Faraday was designed for battle. (The occasion had never arisen, but who knew what might someday emerge from a gate? Besides, her high maneuverability fitted her for rescue work and for conveying exploratory teams.)

"I'm trying to do our best for our government, sir."

"I wish you would tell me who in the government."

"I'm sorry, but I'm only an astronautical officer. It wouldn't be proper for me to discuss politics. Uh, you do see, don't you, you've nothing to worry about? This is an extra precaution, no more."

"Yes, yes," Langendijk sighed. "Let us get on with it." Talk went into technicalities.

Signoff followed. Langendijk addressed his crew: "You heard, of course. Questions? Comments?"

A burst of indignation and dismay responded; loudest came Frieda von Moltke's "Hollenfeuer und Teufelscheiss!" First Engineer Dairoku Mitsukuri was milder: "This is perhaps highhanded, but we ought not to be detained long. The fact of our arrival will generate enormous public pressure for our release."

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

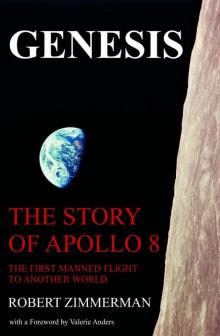

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis