- Home

- Anderson, Poul

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Read online

A KNIGHT OF GHOSTS AND SHADOWS

==============================

Poul Anderson

=============

[22 feb 2003--scanned for #bookz]

[23 feb 2003--proofed for #bookz]

I

-

Every planet in the story is cold--even Terra, though Flandry came home

on a warm evening of northern summer. There the chill was in the spirit.

He felt a breath of it as he neared. Somehow, talk between him and his

son had drifted to matters Imperial. They had avoided all such during

their holiday.

Terra itself had not likely reminded them. The globe hung beautiful in

starry darkness, revealed by a view-screen in the cabin where they sat.

It was almost full, because they were accelerating with the sun behind

them and were not yet close enough to start on an approach curve. At

this remove it shone white-swirled blue, unutterably pure, near dewdrop

Luna. Nothing was visible of the scars that man had made upon it.

And the saloon was good to be in, bulkheads nacreous gray, benches

padded in maroon velvyl, table of authentic teak whereon stood Scotch

whisky and everything needed for the use thereof, warm and flawlessly

recycled air through which gamboled a dance tune and drifted an odor of

lilacs. The Hooligan, private speedster of Captain Sir Dominic Flandry,

was faster, better armed, and generally more versatile than any vessel

of her class had a moral right to be; but her living quarters reflected

her owner's philosophy that, if one is born into an era of decadence,

one may as well enjoy it while it lasts.

He leaned back, inhaled deeply of his cigarette, took more smokiness in

a sip from his glass, and regarded Dominic Hazeltine with some concern.

If the frontier was truly that close to exploding--and the boy must go

there again ... "Are you sure?" he asked. "What proved facts have you

got--proved by yourself, not somebody else? Why wouldn't I have heard

more?"

His companion returned a steady look. "I don't want to make you feel

old," he said; and the knowledge passed through Flandry that a

lieutenant commander of Naval Intelligence, twenty-seven standard years

of age, wasn't really a boy, nor was his father any longer the boy who

had begotten him. Then Hazeltine smiled and took the curse off: "Well, I

might want to, just so I can hope that at your age I'll have acquired,

let alone kept, your capacity for the three basic things in life."

"Three?" Flandry raised his brows. "Feasting, fighting, and--Wait; of

course I haven't been along when you were in a fight. But I've no doubt

you perform as well as ever in that department too. Still, you told me

for the last three years you've stayed in the Solar System, taking life

easy. If the whole word about Dennitza hasn't reached the Emperor--and

apparently it's barely starting to--why should it have come to a

pampered pet of his?"

"Hm. I'm not really. He pampers with a heavy hand. So I avoid the court

as much as politeness allows. This indefinite furlough I'm on--nobody

but him would dare call me back to duty, unless I grow bored and request

assignment--that's the only important privilege I've taken. Aside from

the outrageous amount of talent, capability, and charm with which I was

born; and I do my best to share those chromosomes."

Flandry had spoken lightly in half a hope of getting a similar response.

They had bantered throughout their month-long jaunt, whether on a

breakneck hike in the Great Rift of Mars or gambling in a miners' dive

in Low Venusberg, running the rings of Saturn or dining in elegance

beneath its loveliness on Iapetus with two ladies expert and expensive.

Must they already return to realities? They'd been more friends than

father and son. The difference in age hardly showed. They bore

well-muscled height in common, supple movement, gray eyes, baritone

voice. Flandry's face stood out in a perhaps overly handsome combination

of straight nose, high cheekbones, cleft chin--the result of a biosculp

job many years past, which he had never bothered to change again--and

trim mustache. His sleek seal-brown hair was frosted at the temples;

when Hazeltine accused him of bringing this about by artifice, he had

grinned and not denied it. Though both wore civilian garb, Flandry's

iridescent puff-sleeved blouse, scarlet cummerbund, flared blue

trousers, and curly-toed beefleather slippers opposed the other's plain

coverall.

Broader features, curved nose, full mouth, crow's-wing locks recalled

Persis d'Io as she had been when she and Flandry said farewell on a

planet now destroyed, he not knowing she bore his child. The tan of

strange suns, the lines creased by squinting into strange weathers, had

not altogether gone from Hazeltine in the six weeks since he reached

Terra. But his unsophisticated ways meant only that he had spent his

life on the fringes of the Empire. He had caroused with a gusto to match

his father's. He had shown the same taste in speech--

("--an itchy position for me, my own admiral looking for a nice lethal

job he could order me to do," Flandry reminisced. "Fenross hated my

guts. He didn't like the rest of me very much, either. I saw I'd better

produce a stratagem, and fast."

("Did you?" Hazeltine inquired.

("Of course. You see me here, don't you? It's practically a sine qua non

of a field agent staying alive, that he be able to outthink not just the

opposition, but his superiors."

("No doubt you were inspired by the fact that 'stratagem' spelled

backwards is 'megatarts.' The prospect of counting your loose women by

millions should give plenty of incentive."

(Flandry stared. "Now I'm certain you're my bairn! Though to be frank,

that awesomely pleasant notion escaped me. Instead, having developed my

scheme, I confronted a rather ghastly idea which has haunted me ever

afterward: that maybe there's no one alive more intelligent than I.")

--and yet, and yet, an underlying earnestness always remained with him.

Perhaps he had that from his mother: that, and pride. She'd let the

infant beneath her heart live, abandoned her titled official lover,

resumed her birthname, gone from Terra to Sassania and started anew as a

dancer, at last married reasonably well, but kept young Dominic by her

till he enlisted. Never had she sent word back from her frontier home,

not when Flandry well-nigh singlehanded put down the barbarians of

Scotha and was knighted for it, not when Flandry well-nigh singlehanded

rescued the new Emperor's favorite granddaughter and headed off a

provincial rebellion and was summoned Home to be rewarded. Nor had her

son, who always knew his father's name, called on him until lately, when

far enough along in his own career that nepotism could not be thought

necessary.

Thu

s Dominic Hazeltine refused the offer of merry chitchat and said in

his burred un-Terran version of Anglic, "Well, if you've been taking

what amounts to a long vacation, the more reason why you wouldn't have

kept trace of developments. Maybe his Majesty simply hasn't been

bothering you about them, and has been quite concerned himself for quite

some while. Regardless, I've been yonder and I know."

Flandry dropped the remnant of his cigarette in an ash-taker. "You wound

my vanity, which is no mean accomplishment," he replied. "Remember, for

three or four years earlier--between the time I came to his notice and

the time we could figure he was planted on the throne too firmly to have

a great chance of being uprooted--I was one of his several right hands.

Field and staff work both, specializing in the problem of making the

marches decide they'd really rather keep Hans for their Emperor than

revolt all over again. Do you think, if he sees fresh trouble where I

can help, he won't consult me? Or do you think, because I've been

utilizing a little of the hedonism I fought so hard to preserve, I've

lost interest in my old circuits? No, I've followed the news, and an

occasional secret report."

He stirred, tossed off his drink, and added, "Besides, you claim the

Gospodar of Dennitza is our latest problem child. But you've also said

you were working Sector Arcturus: almost diametrically opposite, and

well inside those vaguenesses we are pleased to call the borders of the

Empire. Tell me, then--you've been almighty unspecific about your

operations, and I supposed that was because you were under security, and

didn't pry--tell me, as far as you're allowed, what does the space

around Arcturus have to do with Dennitza? With anything in the Taurian

Sector?"

"I stayed mum because I didn't want to spoil this occasion," Hazeltine

said. "From what Mother told me, I expected fun, when I could get a

leave long enough to justify the trip to join you; but you've opened

whole universes to me that I never guessed existed." He flushed. "If I

ever gave any thought to such things, I self-righteously labeled them

Vice.'"

"Which they are," Flandry put in. "What you bucolic types don't realize

is that worthwhile vice doesn't mean lolling around on cushions eating

drugged custard. How dismal! I'd rather be virtuous. Decadence requires

application. But go on."

"We'll land now, and I'll report back," Hazeltine said. "I don't know

where they'll send me next, and doubtless won't be free to tell you.

While the chance remains, I'll be honest. I came here wanting to know

you as a man, but also wanting to, oh, alert you if nothing else,

because I think your brains will be sorely needed, and it's damn hard to

communicate through channels."

Indeed, Flandry admitted.

His gaze went to the stars in the viewscreeen. Without amplification,

few that he could see lay in the more or less 200-light-year radius of

that rough and blurry-edged spheroid named the Terran Empire. Those were

giants, visible by virtue of shining across distances we can traverse,

under hyperdrive, but will never truly comprehend; and they filled the

merest, tiniest fragment of the galaxy, far out in a spiral arm where

their numbers were beginning to thin toward cosmic hollowness. Yet this

insignificant Imperial bit of space held an estimated four million suns.

Maybe half of those had been visited at least once. About a hundred

thousand worlds of theirs might be considered to belong to the Empire,

though for most the connection was ghostly tenuous ... It was too much.

There were too many environments, races, cultures, lives, messages. No

mind, no government could know the whole, let alone cope.

Nevertheless that sprawl of planets, peoples, provinces, and

protectorates must somehow cope, or see the Long Night fall. Barbarians,

who had gotten spaceships and nuclear weapons too early in their

history, prowled the borders; the civilized Roidhunate of Merseia

probed, withdrew a little--seldom the whole way--waited, probed again

... Rigel caught Flandry's eye, a beacon amidst the great enemy's

dominions. The Taurian Sector lay in that direction, fronting the

Wilderness beyond which dwelt the Merseians.

"You must know something I don't, if you claim the Dennitzans are

brewing trouble," he said. "However, are you sure what you know is

true?"

"What can you tell me about them?" Hazeltine gave back.

"Hm? Why--um, yes, that's sensible, first making clear to you what

information and ideas I have."

"Especially since they must reflect what the higher-ups believe, which

I'm not certain about."

"Neither am I, really. My attention's been directed elsewhere, Tauria

seeming as reliably under control as any division of the Empire."

"After your experience there?"

"Precisely on account of it. Very well. We'll save time if I run

barefoot through the obvious. Then you needn't interrogate me, groping

around for what you may not have suspected hitherto."

Hazeltine nodded. "Besides," he said, "I've never been in those parts

myself."

"Oh? You mentioned assignments which concerned the Merseia-ward frontier

and our large green playmates."

"Tauria isn't the only sector at that end of the Empire," Hazeltine

pointed out.

Too big, this handful of stars we suppose we know ... "Ahem." Flandry

took the crystal decanter. A refill gurgled into his glass. "You've

heard how I happpened to be in the neighborhood when the governor, Duke

Alfred of Varrak, kidnapped Princess Megan while she was touring, as

part of a scheme to detach the Taurian systems from the Empire and bring

them under Merseian protection--which means possession. Chives and I

thwarted him, or is 'foiled' a more dramatic word?

"Well, then the question arose, what to do next? Let me remind you, Hans

had assumed, which means grabbed, the crown less than two years earlier.

Everything was still in upheaval. Three avowed rivals were out to

replace him by force of arms, and nobody could guess how many more would

take an opportunity that came along, whether to try for supreme power or

for piratical autonomy. Alfred wouldn't have made his attempt without

considerable support among his own people. Therefore, not only must the

governorship change, but the sector capital.

"Now Dennitza may not be the most populous, wealthy, or up-to-date

human-colonized planet in Tauria. However, it has a noticeable sphere of

influence. And it has strength out of proportion, thanks to

traditionally maintaining its own military, under the original treaty of

annexation. And the Dennitzans always despised Josip. His tribute

assessors and other agents he sent them, through Duke Alfred, developed

a tendency to get killed in brawls, and somehow nobody afterward could

identify the brawlers. When Josip died, and the Policy Board split on

accepting his successor, and suddenly all hell let out for noon, the

Gospodar declared for Hans Molitor. He didn't actually dispatch troops

&nbs

p; to help, but he kept order in his part of space, gave the Merseians no

opening--doubtless the best service he could have rendered.

"Wasn't he the logical choice to take charge of Tauria? Isn't he still?"

"In spite of Merseians on his home planet?" Hazeltine challenged.

"Citizens of Merseian descent," Flandry corrected. "Rather remote

descent, I've heard. There are humans who serve the Roidhunate, too, and

not every one has been bought or brainscrubbed; some families have lived

on Merseian worlds for generations."

"Nevertheless," Hazeltine said, "the Dennitzan culture isn't

Terran--isn't entirely human. Remember how hard the colonists of Avalon

fought to stay in the Domain of Ythri, way back when the Empire waged a

war to adjust that frontier? Why should Dennitzans feel brotherly toward

Terrans?"

"I don't suppose they do." Flandry shrugged. "I've never visited them

either. But I've met other odd human societies, not to speak of

nonhuman. They stay in the Empire because it gives them the Pax and

often a fair amount of commercial benefit, without usually charging too

high a price for the service. From what little I saw and heard in the

way of reports on the Gospodar and his associates, they aren't such

fools as to imagine they can stay at peace independently. Their history

includes the Troubles, and their ancestors freely joined the Empire when

it appeared."

"Nowadays Merseia might offer them a better deal."

"Uh-uh. They've been marchmen up against Merseia far too long. Too many

inherited grudges."

"Such things can change. I've known marchmen myself. They take on the

traits of their enemies, and eventually--" Hazeltine leaned across the

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

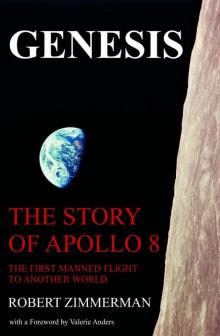

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis