- Home

- Anderson, Poul

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Page 2

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Read online

Page 2

table. His voice harshened. "Why are the Dennitzans resisting the

Emperor's decree?"

"About disbanding their militia?" Flandry sipped. "Yes, I know, the

Gospodar's representatives here have been appealing, arguing,

logrolling, probably bribing, and certainly making nuisances of

themselves on governmental levels as high as the Policy Board. Meanwhile

he drags his feet. If the Emperor didn't have more urgent matters on

deck, we might have seen fireworks by now."

"Nuclear?"

"Oh, no, no. Haven't we had our fill of civil war? I spoke

metaphorically. And ... between us, lad, I can't blame the Gospodar very

much. True, Hans' idea is that consolidating all combat services may

prevent a repetition of what we just went through. I can't say it won't

help; nor can I say it will. If nothing else, the Dennitzans do nest way

out on a windy limb. They have more faith in their ability to protect

themselves, given Navy support, than in the Navy's ability to do it

alone. They may well be right. This is too serious a matter--a whole

frontier is involved--too serious for impulsive action: another reason,

I'm sure, why Hans has been patient, has not dismissed the Gospodar as

governor or anything."

"I believe he's making a terrible mistake," Hazeltine said.

"What do you think the Dennitzans have in mind, then?"

"If not a breakaway, and inviting the Merseians in--I'm far from

convinced that that's unthinkable to them, but I haven't proof--if not

that, then insurrection ... to make the Gospodar Emperor."

Flandry sat still for a while. The ship murmured, the music sang around

him. Terra waxed in his sight.

Finally, taking forth a fresh cigarette, he asked, "What gives you that

notion? Your latest work didn't bring you within a hundred parsecs of

Dennitza, did it?"

"No." Hazeltine's mouth, which recalled the mouth of Persis, drew into

thinner lines than ever hers had done. "That's what scares me. You see,

we've collected evidence that Dennitzans are engineering a rebellion on

Diomedes. Have you heard of Diomedes?"

"Ye-e-es. Any man who appreciates your three primaries of life ought to

study the biography of Nicholas van Rijn, and he was shipwrecked there

once. Yes, I know a little. But it isn't a terribly important planet to

this day, is it? Why should it revolt, and how could it hope to

succeed?"

"I wasn't on that team myself. But my unit was carrying out related

investigations in the same sector, and we exchanged data. Apparently the

Diomedeans--factions among them--hope the Domain of Ythri will help.

They've acquired a mystique about the kinship of winged beings ...

Whether the Ythrians really would intervene or not is hard to tell. I

suspect not, to the extent that'd bring on overt conflict with us. But

they might well use the potentiality, the threat, to steer us into new

orbits--We've barely started tracing the connections."

Flandry scowled. "And those turn out to be Dennitzan?"

"Correct. Any such conspiracy would have to involve members of a society

with spaceships--preferably humans--to plant and cultivate the seed on

Diomedes, and maintain at least enough liaison with Ythri that the

would-be rebels stay hopeful. When our people first got on the track of

this, they naturally assumed the humans were Avalonian. But a lucky

capture they made, just before I left for Sol, indicated otherwise.

Dennitzan agents, Dennitzan."

"Why, on the opposite side of Terra from their home?"

"Oh, come on! You know why. If the Gospodar's planning an uprising of

his own, what better preliminary than one in that direction?" Hazeltine

drew breath. "I don't have the details. Those are, or will be, in the

reports to GHQ from our units. But isn't something in the Empire always

going wrong? The word is, his Majesty plans to leave soon for Sector

Spica, at the head of an armada, and curb the barbarians there. That's a

long way from anyplace else. Meanwhile, how slowly do reports from an

obscure clod like Diomedes grind their way through the bureaucracy?"

"When a fleet can incinerate a world," Flandry said bleakly, "I prefer

governments not have fast reflexes. You and your teammates could well be

quantum-hopping to an unwarranted conclusion. For instance, those

Dennitzans who were caught, if they really are Dennitzans, could be

freebooters. Or if they have bosses at home, those bosses may be a

single clique--may be, themselves, maneuvering to overthrow the

Gospodar--and may or may not have ambitions beyond that. How much more

than you've told me do you know for certain?"

Hazeltine sighed. "Not much. But I hoped--" He looked suddenly,

pathetically young. "I hoped you might check further into the question."

Chives entered, on bare feet which touched the carpet soundlessly though

the gee-field was set at Terran standard. "I beg your pardon, sir," he

addressed his master. "If you wish dinner before we reach the landing

approach zone, I must commence preparations. The tournedos will

obviously require a red wine. Shall I open the Chateau Falkayn '35?"

"Hm?" Flandry blinked, recalled from darker matters. "Why ... um-m ...

I'd thought of Beaujolais."

"No, sir," said Chives, respectfully immovable. "I cannot recommend

Beaujolais to accompany a tournedos such as is contemplated. And may I

suggest drinking and smoking cease until your meal is ready?"

Summer evening around Catalina deepened into night. Flandry sat on a

terrace of the lodge which the island's owner, his friend the Mayor

Palatine of Britain, had built on its heights and had lent to him. He

wasn't sleepy; during the space trip, his circadian rhythm had slipped

out of phase with this area. Nor was he energetic. He felt--a bit

sad?--no, pensive, lonesome, less in an immediate fashion than as an

accumulation from the years--a mood he had often felt before and

recognized would soon become restlessness. Yet while it stayed as it

was, he could wonder if he should have married now and then. Or even for

life? It would have been good to help young Dominic grow.

He sighed, twisted about in his lounger till he found a comfortable

knees-aloft position, drew on his cigar and watched the view. Beneath

him, shadowy land plunged to a bay and, beyond, the vast metallic sheet

of a calm Pacific. A breeze blew cool, scented with roses and Buddha's

cup. Overhead, stars twinkled forth in a sky that ranged from amethyst

to silver-blue. A pair of contrails in the west caught the last glow of

a sunken sun. But the evening was quiet. Traffic was never routed near

the retreats of noblemen.

How many kids do I have? And how many of them know they're mine? (I've

only met or heard of a few.) And where are they and what's the universe

doing to them?

Hm. He pulled rich smoke across his tongue. When a person starts

sentimentalizing, it's time either to get busy or to take antisenescence

treatments. Pending this decision, how about a woman? That stopover on

Ceres was several days ago, after all. He considered ladies he knew and

de

cided against them, for each would expect personal

consideration--which was her right, but his mind was still too full of

his son. Therefore: Would I rather flit to the mainland and its bright

lights, or have Chives phone the nearest cepheid agency?

As if at a signal, his personal servant appeared, a Shalmuan, slim

kilt-clad form remarkably humanlike except for 140 centimeters of

height, green skin, hairlessness, long prehensile tail, and, to be sure,

countless more subtle variations. On a tray he carried a visicom

extension, a cup of coffee, and a snifter of cognac. "You have a call,

sir," he announced.

How many have you filtered out? Flandry didn't ask. Nor did he object.

The nonhuman in a human milieu--or vice versa--commonly appears as a

caricature of a personality, because those around him cannot see most of

his soul. But Chives had attended his boss for years. "Personal servant"

had come to mean more than "valet and cook"; it included being butler of

a household which never stayed long in a single place, and pilot, and

bodyguard, and whatever an emergency might require.

Chives brought the lounger table into position, set down the tray, and

disappeared again. Flandry's pulse bounced a little. In the screen

before him was the face of Dominic Hazeltine. "Why, hello," he said. "I

didn't expect to hear from you this soon."

"Well"--excitement thrummed--"you know, our conversation--When I came

back to base, I got a chance at a general data scanner, and keyed for

recent material on Dennitza. A part of what I learned will interest you,

I think. Though you'd better act fast."

II

--

Immediately after the two Navy yeomen who brought Kossara to the slave

depot had signed her over to its manager and departed, he told her:

"Hold out your left arm." Dazed--for she had been whisked from the ship

within an hour of landing on Terra, and the speed of the aircar had

blurred the enormousness of Archopolis--she obeyed. He glanced expertly

at her wrist and, from a drawer, selected a bracelet of white metal,

some three centimeters broad and a few millimeters thick. Hinged, it

locked together with a click. She stared at the thing. A couple of

sensor spots and a niello of letters and numbers were its only

distinctions. It circled her arm snugly though not uncomfortably.

"The law requires slaves to wear this," the manager explained in a bored

tone. He was a pudgy, faintly greasy-looking middle-aged person in whose

face dwelt shrewdness.

That must be on Terra, trickled through Kossara's mind. Other places

seem to have other ways. And on Dennitza we keep no slaves ...

"It's powered by body heat and maintains an audiovisual link to a global

monitor net," the voice went on. "If the computers notice anything

suspicious--including, of course, any tampering with the bracelet--they

call a human operator. He can stop you in your tracks by a signal." The

man pointed to a switch on his desk. "This gives the same signal."

He pressed. Pain burned like lightning, through flesh, bone, marrow,

until nothing was except pain. Kossara fell to her knees. She never knew

if she screamed or if her throat had jammed shut.

He lifted his hand and the anguish was gone. Kossara crouched shaking

and weeping. Dimly she heard: "That was five seconds' worth. Direct

nerve stim from the bracelet, triggers a center in the brain. Harmless

for periods of less than a minute, if you haven't got a weak heart or

something. Do you understand you'd better be a good girl? All right, on

your feet."

As she swayed erect, the shudders slowly leaving her, he smirked and

muttered, "You know, you're a looker. Exotic; none of this standardized

biosculp format. I'd be tempted to bid on you myself, except the price

is sure to go out of my reach. Well ... hold still."

He did no more than feel and nuzzle. She endured, thinking that probably

soon she could take a long, long, long hot shower. But when a guard had

conducted her to the women's section, she found the water was cold and

rationed. The dormitory gaped huge, echoing, little inside it other than

bunks and inmates. The mess was equally barren, the food adequate but

tasteless. Some twenty prisoners were present. They received her kindly

enough, with a curiosity that sharpened when they discovered she was

from a distant planet and this was her first time on Terra. Exhausted,

she begged off saying much and tumbled into a haunted sleep.

The next morning she got a humiliatingly thorough medical examination. A

psychotech studied the dossier on her which Naval Intelligence had

supplied, asked a few questions, and signed a form. She got the

impression he would have liked to inquire further--why had she

rebelled?--but a Secret classification on her record scared him off. Or

else (because whoever bought her would doubtless talk to her about it)

he knew from his study how chaotic and broken her memories of the

episode were, since the hypnoprobing on Diomedes.

That evening she couldn't escape conversation in the dormitory. The

women clustered around and chattered. They were from Terra, Luna, and

Venus. With a single exception, they had been sentenced to limited terms

of enslavement for crimes such as repeated theft or dangerous

negligence, and were not very bright or especially comely.

"I don't suppose anybody'll bid on me," lamented one. "Hard labor for

the government, then."

"I don't understand," said Kossara. Her soft Dennitzan accent intrigued

them. "Why? I mean, when you have a worldful of machines, every kind of

robot--why slaves? How can it ... how can it pay?"

The exceptional woman, who was handsome in a haggard fashion, answered.

"What else would you do with the wicked? Kill them, even for tiny

things? Give them costly psychocorrection? Lock them away at public

expense, useless to themselves and everybody else? No, let them work.

Let the Imperium get some money from selling them the first time, if it

can."

Does she talk like that because she's afraid of her bracelet? Kossara

wondered. Surely, oh, surely we can complain a little among ourselves!

"What can we do that a machine can't do better?" she asked.

"Personal services," the woman said. "Many kinds. Or ... well,

economics. Often a slave is less efficient than a machine, but needs

less capital investment."

"You sound educated," Kossara remarked.

The woman sighed. "I was, once. Till I killed my husband. That meant a

life term like yours, dear. To be quite safe, my buyer did pay to have

my mind corrected." A sort of energy blossomed in look and tone. "How

grateful I am! I was a murderess, do you hear, a murderess. I took it on

myself to decide another human being wasn't fit to live. Now I know--"

She seized Kossara's hands. "Ask them to correct you too. You committed

treason, didn't you say? Beg them to wash you clean!"

The rest edged away. Brain-channeled, Kossara knew. A crawling went

under her skin. "Wh-why are you here?" she stammered. "If you were

bought--"

/> "He grew tired of me and sold me back. I'll always long for him ... but

he had the perfect right, of course." The woman drew nearer. "I like

you, Kossara," she whispered. "I do hope we'll go to the same place."

"Place?"

"Oh, somebody rich may take you for a while. Likelier, though, a

brothel--"

Kossara yanked free and ran. She didn't quite reach a toilet before she

vomited. They made her clean the floor. Afterward, when they insisted on

circling close and talking and talking, she screamed at them to leave

her alone, then enforced it with a couple of skilled blows. No

punishment followed. It was dreadful to know that a half-aware

electronic brain watched every pulsebeat of her existence, and no doubt

occasionally a bored human supervisor examined her screen at random. But

seemingly the guardians didn't mind a fight, if no property was damaged.

She sought her bunk and curled up into herself.

Next morning a matron came for her, took a critical look, and nodded.

"You'll do," she said. "Swallow this." She held forth a pill.

"What's that?" Kossara crouched back.

"A euphoriac. You want to be pretty for the camera, don't you? Go on,

swallow." Remembering the alternative, Kossara obeyed.

As she accompanied the matron down the hall, waves of comfort passed

through her, higher at each tide. It was like being drunk, no, not

drunk, for she had her full senses and command of her body ... like

having savored a few glasses with Mihail, after they had danced, and the

violins playing yet ... like having Mihail here, alive again.

Almost cheerfully, in the recording room she doffed her gray issue gown,

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

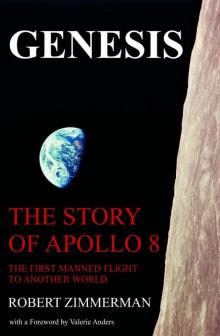

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis