- Home

- Anderson, Poul

Queen Of Air & Darkness Page 2

Queen Of Air & Darkness Read online

Page 2

"hiring someone else as well qualified would be prohibitively

expensive, on a pioneer planet where every hand has a thousand

urgent tasks to do. Besides, you have a motive. And I'll need that. 1,

who was born on another world altogether strange to this one, itself

altogether strange to Mother Earth, I am too dauntingly aware of how

handicapped we are."

Night gathered upon Christmas Landing. The air stayed mild, but

glimmer-lit tendrils of fog, sneaking through the streets, had a cold

look, and colder yet was the aurora where it shuddered between the

moons. The woman drew closer to the man in this darkening room,

surely not aware that she did, until he switched on a Auoropanel. The

same knowledge of Roland's aloneness was in both of them.

One light-year is not much as galactic distances go. You could walk it

in about 270 million years, beginning at the middle of the Permian

Era, when dinosaurs belonged to the remote future, and continuing to

the present day when spaceships cross even greater reaches. But stars

in our neighborhood average some nine lightyears apart, and barely

one percent of them have planets which are man-habitable, and speeds

are limited to less than that of radiation. Scant help is given by

relativistic time contraction and suspended animation en route.' These

make the journeys seem short, but history meanwhile does not stop at

home.

Thus voyages from sun to sun will always be few. Colonists will be

those who have extremely special reasons for going. They will take

along germ plasm for exogenetic cultivation of domestic plants and

animals-and of human infants, in order that population can grow fast

enough to escape death through genetic drift. After all, they cannot

rely on further immigration. Two or three

times a century, a ship may call from some other colony. (Not from

Earth. Earth has long ago sunk into alien concerns.) Its place of origin

will be an old settlement. The young ones are in no position to build

and man interstellar vessels.

Their very survival, let alone their eventual modernization, is in

doubt. The founding fathers have had to take what they could get in a

universe not especially designed for man.

Consider, for example, Roland. It is among the rare happy finds, a

world where humans can live, breathe, eat the food, drink the water,

walk unclad if they choose, sow their crops, pasture their beasts, dig

their mines, erect their homes, raise their children and grandchildren.

It is worth crossing three-quarters of a light-century to preserve

certain dear values and strike new roots into the soil of Roland.

But the star Charlemagne is of type F9, forty percent brighter than

Sol, brighter still in the treacherous ultraviolet and wilder still in the

wind of charged particles that seethes from it. The planet has an

eccentric orbit. In the middle of the short but furious northern

summer, which includes periastron, total insolation is more than

double what Earth gets; in the depth of the long northern winter, it is

barely less than Terrestrial average.

Native life is abundant everywhere. But lacking elaborate machinery,

not yet economically possible to construct for more than a few

specialists, man can only endure the high latitudes. A tendegree axial

tilt, together with the orbit, means that the northern part of the

Arctican continent spends half its year in unbroken sunlessness.

Around the South Pole lies an empty ocean.

Other differences from Earth might superficially seem more

important. Roland has two moons, small but close, to evoke clashing

tides. It rotates once in thirty-two hours, which is endlessly, subtly

disturbing to organisms evolved through gigayears of a quicker

rhythm. The weather patterns are altogether unterrestrial. The globe

is a mere 9500 kilometers in diameter; its surface gravity is 0.42 X

980 cm/sect; the sea level air pressure is slightly above one Earth

atmosphere. (For actually Earth is the freak, and

man exists because a cosmic accident blew away most of the gas that a

body its size ought to have kept, as Venus has done.)

However, Homo can truly be called sapiens when he practices his

specialty of being unspecialized. His repeated attempts to freeze

himself into an all-answering pattern or culture or ideology, or

whatever he has named it, have repeatedly brought ruin. Give him the

pragmatic business of making his living, and he will usually do rather

well. fie adapts, within broad limits.

These limits are set by such factors as his need for sunlight and his

being, necessarily and forever, a part of the life that surrounds him and

a creature of the spirit within.

Portolondon thrust docks, boats, machinery, warehouses into the Gulf

of Polaris. Behind them huddled the dwellings of its five thousand

permanent inhabitants: concrete walls, storm shutters, high-peaked tile

roofs. The gaiety of their paint looked forlorn amidst lamps; this town

lay past the Arctic Circle.

Nevertheless Sherrinford remarked, "Cheerful place, eh? The kind of

thing I came to Roland looking for."

Barbro made no reply. The days in Christmas Landing, while he made

his preparations, had drained her. Gazing out the dome of the taxi that

was whirring them downtown from the hydrofoil that brought them,

she supposed he meant the lushness of forest and meadows along the

road, brilliant hues and phosphorescence of flowers in gardens, clamor

of wings overhead. Unlike Terrestrial flora in cold climates, Arctican

vegetation spends every, daylit hour in frantic growth and energy

storage. Not till summer's fever gives place to gentle winter does it

bloom and fruit; and estivating animals rise from their dens and

migratory birds come home.

The view was lovely, she had to admit: beyond the trees, a spaciousness

climbing toward remote heights, silvery-gray under a moon, an aurora,

the diffuse radiance from a sun just below the horizon.

Beautiful as a hunting satan, she thought, and as terrible. That

wilderness had stolen Jimmy. She wondered it she would at least

be given to find his little bones and take them to his father.

Abruptly she realized that she and Sherrinford were at their hotel and

that he had been speaking of the town. Since it was next in size after

the capital, he must have visited here often before. The streets were

crowded and noisy; signs flickered, music blared from shops, taverns,

restaurants, sports centers, dance halls; vehicles were jammed down to

molasses speed; the several-storieshigh office buildings stood aglow.

Portolondon linked an enormous hinterland to the outside world. Down

the Gloria River came timber rafts, ores, harvest of farms whose

owners were slowly making Rolandic life serve them, meat and ivory

and furs gathered by rangers in the mountains beyond Troll Scarp. In

from the sea came coastwise freighters, the fishing fleet, produce of

the Sunward Islands, plunder of whole continents further south where

bold men adventured. It clanged in Portolondon,

laughed, blustered,

swaggered, connived, robbed, preached, guzzled, swilled, toiled,

dreamed, lusted, built, destroyed, died, was born, was happy, angry,

sorrowful, greedy, vulgar, loving, ambitious, human. Neither the sun's

blaze elsewhere nor the half year's twilight here-wholly night around

midwinter-was going to stay man's hand.

Or so everybody said.

Everybody except those who had settled in the darklands. Barbro used

to take for granted that they were evolving curious customs, legends

and superstitions, which would die when the Outway had been

completely mapped and controlled. Of late, she had wondered. Perhaps

Sherrinford's hints, about a change in his own attitude brought about by

his preliminary research; were responsible.

Or perhaps she just needed something to think about besides how

Jimmy, the day before he went, when she asked him whether he wanted

rye or French bread for a sandwich, answered in great solemnity-he was

becoming interested in the alphabet "I'll have a slice of what we people

call the F bread."

She scarcely noticed getting out of the taxi, registering, being

conducted to a primitively furnished room. But after she unpacked, she

remembered Sherrinford had suggested a confidential conference. She

went down the hall and knocked on his door. Her knuckles sounded less

loud than her heart.

He opened the door, finger on lips, and gestured her toward a corner.

Her temper bristled until she saw the image of Chief Constable Dawson

in the visiphone. Sherrinford must have chimed him up and must have

a reason to keep her out of scanner range. She found a chair and

watched, nails digging into knees.

The detective's lean length refolded itself. "Pardon the interruption,"

he said. "A man mistook the number. Drunk, by the indications."

Dawson chuckled. "We get plenty of those." Barbro recalled his

fondness for gabbing. He tugged the beard which he affected, as if he

were an outwayer instead of a townsman. "No harm in them as a rule.

They only have a lot of voltage to discharge, after weeks or months in

the backlands.".

"I've gathered that that environment-foreign in a million major and

minor ways to the one that created man-I've gathered that it does do

odd things to the personality." Sherrinford tamped his pipe. "Of

course, you know my practice has been confined to urban and suburban

areas. Isolated garths seldom need private investigators. Now that

situation appears to have changed. I called to ask you for advice."

"Glad to help," Dawson said. "I've not forgotten what you did for us in

the de Tahoe murder case." Cautiously: "Better explain your problem

first."

Sherrinford struck fire. The smoke that followed cut through the green

odors-even here, a paved pair of kilometers from the nearest woods-

that drifted past traffic rumble through a crepuscular window. "This is

more a scientific mission than a search for an absconding debtor or an

industrial spy," he drawled. "I'm looking into two possibilities: that an

organization, criminal or religious or whatever, has long been active

and steals infants; or that the Outlings of folklore are real."

"Huh?" On Dawson's face Barbro read as much dismay as surprise.

"You can't be serious!"

"Can't I?" Sherrinford smiled. "Several generations' worth of reports

shouldn't be dismissed out of hand. Especially not when they become

more frequent and consistent in the course of time, not less. Nor can

we ignore the documented loss of babies and small children, amounting

by now to over a hundred, and never a trace found afterward. Nor the

finds which demonstrate that an intelligent species once inhabited

Arctica and may still haunt the interior."

Dawson leaned forward as if to climb out of the screen. "Who engaged

you?" he demanded. "That Cullen woman? We were sorry for her,

naturally, but she wasn't making sense, and when she got downright

abusive-"

"Didn't her companions, reputable scientists, confirm her story?"

"No story to confirm. Look, they had the place ringed with detectors

and alarms, and they kept mastiffs. Standard procedure in country

where a hungry sauroid or whatever might happen by Nothing could've

entered unbeknownst."

"On the ground. flow about a flyer landing in the middle of camp?"

"A man in a copter rig would've roused everybody."

"A winged being might be quieter."

"A living flyer that could lift a three-year-old boy? Doesn't exist."

"Isn't in the scientific literature, you mean, Constable. Remember

Graymantle; remember how little we know about Roland, a planet, an

entire world. Such birds do exist on Beowulf-and on Rustum, I've read. I

made a calculation from the local ratio of air density to gravity, and,

yes, it's marginally possible here too. The child could have been carried

off for a short distance before wing muscles were exhausted and the

creature must descend."

Dawson snorted. "First it landed and walked into the tent where

mother and boy were asleep. Then it walked away, toting

him, after it couldn't fly further. Does that sound like a bird of prey?

And the victim didn't cry out, the dogs didn't bark!"

"As a matter of fact," Sherrinford said, "those inconsistencies are the

most interesting and convincing features of the whole account. You're

right, it's hard to see how a human kidnapper could get in undetected,

and an eagle type of creature wouldn't operate in that fashion. But none

of this applies to a winged intelligent being. The boy could have been

drugged. Certainly the dogs showed signs of having been."

"The dogs showed signs of having overslept. Nothing had disturbed

them. The kid wandering by wouldn't do so. We don't need to assume

one damn thing except, first, that he got restless and, second, that the

alarms were a bit sloppily rigged-seeing as how no danger was expected

from inside camp-and let him pass out. And, third, I hate to speak this

way, but we must assume the poor tyke starved or was killed."

Dawson paused before adding: "If we had more staff, we could have given

the affair more time. And would have, of course. We did make an aerial

sweep, which risked the lives of the pilots, using instruments which

would've sported the kid anywhere in a fiftykilometer radius, unless he

was dead. You know how sensitive thermal analyzers are. We drew a

complete blank. We have more important jobs than to hunt for the

scattered pieces of a corpse."

He finished brusquely. "If Mrs. Cullen's hired you, my advice is you find

an excuse to quit. Better for her, too. She's got to come to terms with

reality."

Barbro checked a shout by biting her tongue.

"Oh, this is merely the latest disappearance of the series," Sherrinford

said. She didn't understand how he could maintain his easy tone when

Jimmy. was lost. "More thoroughly recorded than any before, thus more

suggestive. Usually an outwayer family has given a tearful but undetailed

account of their child who vanished and must have been stolen by

the

Old Folk. Sometimes, years later, they'd tell about glimpses of what they

swore must have been the grown child, not really human any longer,

flitting past in

murk or peering through, a window or working mischief upon them. As

you say, neither the authorities nor the scientists have had personnel or

resources to mount a proper investigation. But as I say, the matter

appears to be worth investigating. Maybe a private party like myself can

contribute."

"Listen, most of us constables grew up in the outway. We don't just ride

patrol and answer emergency calls; we go back there for holidays and

reunions. If any gang of . . . of human sacrificers was around, we'd

know."

"I realize that. I also realize that the people you came from have a

widespread and deep-seated belief in nonhuman beings with supernatural

powers. Many actually go through rites and make offerings to propitiate

them."

"I know what you're leading up to," Dawson fleered. "I've heard it

before, from a hundred sensationalists. The aborigines are the Outlings. I

thought better of you. Surely you've visited a museum° or three, surely

you've read literature from planets which do have natives-or damn and

blast, haven't you ever applied that logic of yours?"

He wagged a finger. "Think," he said. "What have we in fact discovered?

A few pieces of worked stone; a few megaliths that might be artificial;

scratchings on rock that seem to show plants and animals, though not

the way any human culture would ever have shown them; traces of fires

and broken bones; other fragments of bone that seem as if they might've

belonged to thinking creatures, as if they might've been inside fingers or

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

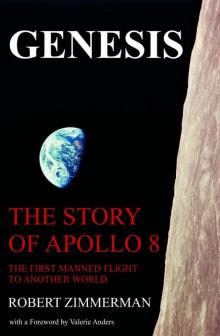

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis