- Home

- Anderson, Poul

Operation Chaos Page 4

Operation Chaos Read online

Page 4

The demon recognized it, too. I imagine the Saracen adept who pumped a knowledge of English into him, to make him effective in this war, had added other bits of information about the modern world. He grew more quiet and attentive.

Virginia intoned impressively: "I can speak nothing to you except the truth. Do you agree that the name is the thing?"

"Y‑y‑yes," the afreet rumbled. "That is common knowledge."

I scented her relief. First hurdle passed! He had not been educated in scientific goetics. Though the name is, of course, in sympathy with the object, which is the principle of nymic spells and the like?‑nevertheless, only in this century has Korzybski demonstrated that the word and its referent are not identical. ,

"Very well," she said. "My name is Ginny."

He started in astonishment. "Art thou indeed?"

"Yes. Now will you listen to me? I came to offer you advice, as one jinni to another. I have powers of my own, you ]snow, albeit I employ them in the sere vice of Allah, the Omnipotent, the Omniscient, the Compassionate."

He glowered, but supposing her to be one of his species, he was ready to put on a crude show of courtesy. She couldn't be lying about her advice. It did not occur to him that she hadn't said the counsel would be good.

"Go on, then, if thou wilst," he growled. "Knowest thou that tomorrow I fare forth to destroy the infidel host?" He got caught up in his dreams of glory. "Aye, well will I rip them, and trample them, and break and gut and flay them. Well will they learn the power of Rashid the bright‑winged, the fiery, the merciless, the wise, the . . ."

Virginia waited out his adjectives, then said gently: "But Rashid, why must you wreak harm? You earn nothing thereby except hate."

A whine crept into his bass. "Aye, thou speakest sooth. The whole world hates me. Everybody conspires against me. Had he not had the aid of traitors, Suleiman had never locked me away. All which I have sought to do has been thwarted by envious ill‑wishers. Aye, but tomorrow comes the day of reckoning!"

Virginia lit a cigaret with a steady hand and blew smoke at him. "How can you trust the emir and his cohorts?" she asked. "He too is your enemy. He only wants to make a cat's‑paw of you. Afterward, back in the bottle!"

"Why. . .why. . ." The afreet swelled till the spacewarp barrier creaked. Lightning crackled from his nostrils. It hadn't occurred to him before; his race isn't bright; but of course a trained psychologist would understand how to follow out paranoid logic.

"Have you not known enmity throughout your long days?" continued Virginia quickly. "Think back, Rashid. Was not the very first thing you remember the cruel act of a spitefully envious world?"

"Aye‑it was." The maned head nodded, and the voice dropped very low. "On the day I was hatched . . . aye, my mother's wingtip smote me so I reeled."

"Perhaps that was accidental," said Virginia.

"Nay. Ever she favored my older brother?the lout!"

Virginia sat down cross‑legged. "Tell me about it," she oozed. Her tone dripped sympathy.

I felt a lessening, of the great forces that surged within the barrier. The afreet squatted on his hams, eyes half‑shut, going back down a memory trail of millennia. Virginia guided him, a hint here and there. I didn't know what she was driving at, surely you couldn't psychoanalyze the monster in half a night, but‑

"Aye, and I was scarce turned three centuries when I fell into a pit my foes must have dug for me."

"Surely you could fly out of it," she murmured.

The afreet's eyes rolled. His face twisted into still more gruesome furrows. "It was a pit, I say!"

"Not by any chance a lake?" she inquired.

"Nay!" His wings thundered. "No such damnable thing . . . 'twas dark; and wet, but‑nay, not wet either, a cold which burned . . .

I saw dimly that the girl had a lead. She dropped long lashes to hide the sudden gleam in her gaze. Even as a wolf, I could realize what a shock it must a have been to an aerial demon, nearly drowning, his fires hissing into steam, and how he must ever after deny to himself that it had happened. But what use could she make of‑

Svartalf the cat streaked in and skidded to a halt. Every hair on him stood straight, and his eyes blistered me. He spat something and went out again with me in his van.

Down in the lobby I heard voices. Looking through the door, I saw a few soldiers milling about. They come by, perhaps to investigate the noise, seen the dead guards, and now they must have sent for reinforcements.

Whatever Ginny was trying to do, she needed time for it. I went out that door in one gray leap and tangled with the Saracens. We boiled into a clamorous pile. I was almost pinned flat by their numbers, but kept my jaws free and used them. Then Svartalf rode that broomstick above the fight, stabbing.

We carried a few of their weapons back into the lobby in our jaws, and sat down to wait. I figured I'd do better to remain wolf and be immune to most things than have the convenience of hands. Svartalf regarded a tommy gun thoughtfully, propped it along a wall, and crouched over it.

I was in no hurry. Every minute we were left alone, or held off the coming attack, was a minute gained for Ginny. I laid my head on my forepaws and dozed off. Much too soon I heard hobnails rattle on pavement.

The detachment must have been a good hundred. I saw their dark mass, and the gleam of starlight off their weapons. They hovered for a while around the squad we'd liquidated. Abruptly they whooped and charged up the steps.

Svartalf braced himself and worked the tommy gun. The recoil sent him skating back across the lobby, swearing, but he got a couple. I met the rest in the doorway.

Slash, snap, leap in, leap out, rip them and gash them and howl in their faces! After a brief whirl of teeth they retreated. They left half a dozen dead and wounded.

I peered through the glass in the door and saw my friend the emir. He had a bandage over his eye, but lumbered around exhorting his men with more energy than I'd expected. Groups of them broke from the main bunch and ran to either side. They'd be coming in the windows and the other doors.

I whined as I realized we'd left the broomstick outside. There could be no escape now, not even for Ginny. The protest became a snarl when I heard glass breaking and rifles blowing off locks. That Svartalf was a smart cat. He found the tommy gun again and somehow, clumsy though paws are, managed to shoot out the lights. He and I retreated to the stairway. They came at us in the dark, blind as most men are. I let them fumble around, and the first one who groped to the stairs was killed quietly. The second had time to yell. The whole gang of them crowded after him. They couldn't shoot in the gloom and press without potting their own people. Excited to mindlessness, they attacked me with scimitars, which I didn't object 3 to. Svartalf raked their legs and I tore them apart?whick, snap, clash, Allah-Akbar and teeth in the night!! The stair was narrow enough for me to hold, and their own casualties hampered them, but the sheer weight of a hundred brave men forced me back a tread at a time. Otherwise one could have tackled me and a dozen more have piled on top. As things were, we gave the houris a few fresh customers for every foot we lost.

I have no clear memory of the fight. You seldom do. But it must have been about twenty minutes before they fell back at an angry growl. The emir himself stood at the foot of the stairs, lashing his tail and rippling his gorgeously striped hide.

I shook myself wearily and braced my feet for the last round. The one‑eyed tiger climbed slowly towards us. Svartalf spat. Suddenly he zipped down the banister past the larger cat and disappeared in the gloom. Well, he had his own neck to think about?

We were almost nose to nose when the emir lifted paw full of swords and brought it down. I dodged somehow and flew for his throat. All I got was a mouthful of baggy skin, but I hung on and tried to work my way inward.

He roared and shook his head till I swung like a bell clapper. I shut my eyes and clamped on tight. He raked my ribs with those long claws. I skipped away but kept my teeth where they were. Lunging, he fell on me. His jaws clashed shut. Pain

jagged through my tail. I let go to howl.

He pinned me down with one paw, raising the other to break my spine. Somehow, crazed with the hurt, I writhed free and struck upward. His remaining eye was glaring at me, and I bit it out of his head.

He screamed! A sweep of one paw sent me kiting up to slam against the banister. I lay with the wind knocked from me while the blind tiger rolled over in his agony. The beast drowned the man, and he went down the stairs and wrought havoc among his own soldiers.

A broomstick whizzed above the melee. Good old Svartalf! He'd only gone to fetch our transportation. I saw him ride toward the door of the afreet, and rose groggily to meet the next wave of Saracens.

They were still trying to control their boss. I gulped for breath and stood watching and smelling and listening. My tail seemed, ablaze. Half of it was gone.

A tommy gun began stuttering. I heard blood rattle in the emir's lungs. He was hard to kill. That's the end of you, Steve Matuchek, thought the man of me. They'll do what they should have done in the first place, stand beneath you and sweep you with their fire, every tenth round argent.

The emir fell and lay gasping out his life. I waited for his men to collect their wits and remember me.

Ginny appeared on the landing, astride the broomstick. Her voice seemed to come from very far away. "Steve! Quick! Here!"

I shook my head dazedly, trying to understand. was too tired, too canine. She stuck her forgers in her, mouth and whistled. That fetched me.

She slung me across her lap and hung on tight as Svartalf piloted the stick. A gun fired blindly from below. We went out a second‑story window and into the sky.

A carpet swooped near. Svartalf arched his back and poured on the Power. That Cadillac had legs! We left the enemy sitting there, and I passed out.

VII

WHEN I CAME TO, I was prone on a cot in a hospital tent. Daylight was bright outside; the earth lay wet and steaming. A medic looked around as I groaned. "Hello, hero," he said. "Better stay in that position for a while. How're you feeling?"

I waited till full consciousness returned before I accepted a cup of bouillon. "How am I?" I whispered; they'd humanized me, of course.

"Not too bad, considering. You had some infection of your wounds?a staphylococcus that can switch species for a human or canine host?but we cleaned the bugs out with a new antibiotic technique. Otherwise, loss of blood, shock, and plain old exhaustion. You should be fine in a week or two."

I lay thinking, my mind draggy, most of my attention on how delicious the bouillon tasted. A field hospital can't lug around the equipment to stick pins in model bacteria. Often it doesn't even have the enlarged anatomical dummies on which the surgeon can do a sympathetic operation. "What technique do you mean?" I asked.

"One of our boys has the Evil Eye. He looks at the germs through a microscope."

I didn't inquire further, knowing that Reader's Big would be waxing lyrical about it in a few months Something else nagged at me. "The attack . . . have they begun?"

"The‑ Oh. That! That was two days ago, Rin‑Tin Tin. You've been kept under asphodel. We mopped 'em up along the entire line. Last I heard, they we across the Washington border and still running.'

I sighed and went back to sleep. Even the noise as the medic dictated a report to his typewriter couldn't hold me awake.

Ginny came in the next day, with Svartalf riding he shoulder. Sunlight striking through the tent flap turned her hair to hot copper. "Hello, Captain Matuchek, she said. "I came to see how you were, soon as I couldn't get leave."

I raised myself on my elbows, and whistled at the cigaret she offered. When it was between my lips, said slowly: "Come off it, Ginny. We didn't exactly go on a date that night, but I think we're properly introduced."

"Yes." She sat down on the cot and stroked my hair. That felt good. Svartalf purred at me, and I wished I could respond.

"How about the afreet?" I asked after a while.

"Still in his bottle." She grinned. "I doubt if anybody ever be able to get him out again, assuming anybody would want to."

"But what did you do?"

"A simple application of Papa Freud's principles. it's ever written up, I'll have every Jungian in country on my neck, but it worked. I got him spinning out his memories and illusions, and found he had a hydrophobic complex‑which is fear of water, Rover, not rabies‑" y

"You can call me Rover," I growled, "but if you call me Fido, gives a paddling."

She didn't ask why I assumed I'd be sufficiently close in future for such laying on of hands. That encouraged me. Indeed, she bushed, but went on: "Having gotten the key to his personality, I found it simple to play on his phobia. I pointed out how common a substance water is and how difficult total dehydration is. He got more and more scared. When I showed him that all animal tissue, including his own, is about eighty percent water, that was that. He crept back into his bottle and went catatonic."

After a moment, she added thoughtfully: "I'd like to have him for my mantelpiece, but I suppose he'll wind up in the Smithsonian. So I'll simply write a little treatise on the military uses of psychiatry."

"Aren't bombs and dragons and elfshot gruesome enough?" I demanded with a shudder.

Poor simple elementals! They think they're fiendish, but ought to take lessons from the human race.

As for me, I could imagine certain drawbacks to getting hitched with a witch, but "C'mere, youse."

She did.

I don't have many souvenirs of the war. It was an ugly time and best forgotten. But one keepsake will always be with me, in spite of the plastic surgeons' best efforts. As a wolf, I've got a stumpy tail, and as a man I don't like to sit down in wet weather.

That's a hell of a thing to receive a Purple Heart for.

VIII

HERE WE REACH one of the interludes. I'll skip oveR them fast. They were often more interesting and important to us?to Ginny and me?than the episodes which directly involved our Adversary. The real business of people is not strife or danger or melodrama: it's work, especially if they're so fortunate as to enjoy what they do; it's recreation and falling in love and raising families and telling jokes and stumbling into small pleasant adventures. r

But you wouldn't care especially about what happened to us in those departments. You have your personal lives. Furthermore, a lot of it is nobody's business but ours. Furthermore yet, I have only one night to 'cast. Any longer, and the stress might have effects on me. I don't take needless chances the unknown; I've been there.

Finally, the big events do matter to you. He's also your Adversary.

Let me therefore just use the interludes to put episodes in context. Okay?

This first period covers roughly two years. For several months of them Ginny and I remained in service, though we didn't see combat again. Nor did we see each other, which was worse on two counts. Reassignment kept shuffling us around.

Not that the war lasted that long. The kaftans had been beaten off the Caliphate. It disintegrated like a dropped windowpane, in revolutions, riots, secessions, vendettas, banditry and piecemeal surrenders. America and her allies didn't need armed forces to invade enemy‑held territory. They did need them, and urgently, for its occupation, to restore order before famine and plague broke loose. Our special talents had Ginny and me hopping over half the world‑but not in company.

We spent a barrel of pay on postage. Nevertheless I took a while to decide I really had better propose; and while her answer was tender, it wasn't yes. Orphaned at a rather early age, she'd grown to womanhood with a need for warmth?and a capacity for it which required that tough career‑girl shell to guard her from hurt. She would not contract a marriage that she wasn't certain could be for life.

I was discharged somewhat before her and went home to reweave threads torn loose by the war. Surprisingly few showed in the United States. Though the invaders had overrun nearly half, throughout most of float conquest they were present only a short while before we rolled them back, and in tha

t while we kept them too busy to wreak the degree of harm that luckless longer‑held corners like Trollburg suffered. Civil government followed on the heels of the Army, more rapid and efficient in its work than I'd have expected. Or maybe civilization itself was responsible. Technology can produce widespread devastation, but likewise quick recoveries.

Thus I returned to a country which, apart from various shortages that soon disappeared, looked familiar. On the surface, I mean. The psyche was some thing else again. Shocked to their souls by what had happened, I suppose, shocked more deeply than they knew, a significant part of the population had come unbalanced. What saved us from immediate social disaster was doubtless the variety of their eccentricities. So many demagogues, self‑appointed prophets, would‑be necromancers, nut cultists in religion and politics and science and dieting and life style and, Lord knows what else, tended to cancel each other out. A few of them did grow ominously, like the Johannine Church, of which much more anon.

However, that didn't happen in a revolutionary leap. Those of us who weren't afflicted with some fanaticism?and we were the majority, remember?seldom worried more than peripherally. We figured the body politic would stop twitching in the natural course of events. Meanwhile we had our careers and dreams to rebuild; we had the everydays to get through.

Myself, I went back to Hollywood and resume werewolfing for Metro‑Goldwyn‑Merlin. That proved a disappointment. It was a nuisance wearing a fake brush over my bobbed tail, for me and the studio alike. They weren't satisfied with my performance either; nor was I. For instance, in spite of honest trying, I couldn't get real conviction into my role Dracula, Frankenstein, the Wolf Man, the Mummy and the Thing Meet Paracelsus. Not that I look down on pure entertainment, but I was discovering a newborn wish to do something more significant.

So there began to be mutual hints about my rep nation. Probably only my medals delayed a crisis. 1 war heroes were a dime a coven. Besides, everybody knows that military courage is a large part training and discipline, another large part the antipanic geas; the latter is routinely lifted upon discharge, because civilians need a touch of timidity. I don't claim more than the normal share of natural guts.

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

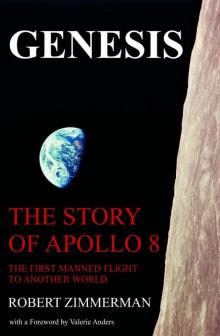

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis