- Home

- Anderson, Poul

Queen Of Air & Darkness Page 5

Queen Of Air & Darkness Read online

Page 5

She nodded. Ile had told her his general plan, which was too obvious to

conceal. The problem was to make contact with the aliens, if they

existed. Hitherto, they had only revealed themselves, at rare

intervals, to one or a few backwoodsmen at a time. An ability to

generate hallucinations would help them in that. They would stay

clear of any large, perhaps unmanageable expedition which might pass

through their territory. But two people, braving all prohibitions,

shouldn't look too formidable to approach. And . . . this would be the

first human team which not only worked on the assumption that the

Outlings were real but possessed the resources of modern, off-planet

police technology.

Nothing happened at that camp. Sherrinford said he hadn't expected it

would. The Old Folk seemed cautious this near to any settlement. In

their own lands they must be bolder.

And by the following "night," the vehicle had gone well into yonder

country. When Sherrinford stopped the engine in a meadow and the

car settled down, silence rolled in like a wave.

They stepped out. She cooked a meal on the glower while he gathered

wood, that they might later cheer themselves with a campfire.

Frequently he glanced at his wrist. It bore no watchinstead, a radio-

controlled dial, to tell what the instruments in the bus might register.

Who needed a watch here? Slow constellations wheeled beyond

glimmering aurora. The moon Alde stood above a snowpeak, turning

it argent, though this place lay at a goodly height. The rest of the

mountains were hidden by the forest that crowded around. Its trees

were mostly shiverleaf and feathery white plumablanca,

ghostly amidst their shadows. A few firethorns glowed, clustered dim

lanterns, and the underbrush was heavy and smelled sweet. You could see

surprisingly far through the blue dusk. Somewhere nearby, a brook sang

and a bird fluted.

"Lovely here," Sherrinford said. They had risen from their supper and

not yet sat down again or kindled their fire.

"But strange," Barbro answered as low. "I wonder if it's really meant for

us. If we can really hope to possess it."

His pipestem gestured at the stars. "Man's gone to stranger places than

this."

"Has he? I . . . oh, I suppose it's just something left over from my outway

childhood, but do you know, when I'm under them I can't think of the.

stars as balls of gas, whose energies have been measured, whose planets

have been walked on by prosaic feet. No, they're small and cold and

magical; our lives are bound to them; after we die, they whisper to us in

our graves." Barbro glanced downward. "I realize that's nonsense."

She could see in the twilight how his face grew tight. "Not at all," he

said.

"Emotionally, physics may be a worse nonsense. And in the end, you

know, after a sufficient number of generations, thought follows feeling.

Man is not at heart rational. He could stop believing the stories of science

if those no longer felt right."

He paused. "That ballad which didn't get finished in the house," he said,

not looking at her. "Why did it affect you so?"

"I couldn't stand hearing them, well, praised. Or that's how it seemed.

Sorry for the fuss."

"I gather the ballad is typical of a large class."

"Well, I never thought to add them up. Cultural anthropology is

something we don't have time for on Roland, or more likely it hasn't

occurred to us, with everything else there is to do. Butnow you mention

it, yes, I'm surprised at how many songs and stories have the Arvid motif

in them."

"Could you bear to recite it?"

She mustered the will to laugh. "Why, I can do better than that if you

want. Let me get my multilyre and I'll perform."

She omitted the hypnotic chorus line, though, when the notes rang out,

except at the end. He watched her where she stood . against moon and

aurora.

`-the Queen of Air and Darkness cried softly under sky:

"'Light down, you ranger Arvid, and join the Outling folk. You need no

more be human, which is a heavy yoke.'

"lie dared to give her answer: I may do naught but run. A maiden waits

me, dreaming in lands beneath the sun.

"'And likewise wait me comrades and tasks I would not shirk, for what is

ranger Arvid if he lays down his work?

"'So wreak your spells, you Outling, and east your wrath on me. Though

maybe you can slay me, you'll not make me unfree.'

"The Queen of Air and Darkness stood wrapped about with fear and

northlight flares and beauty he dared not look too near.

"Until she laughed like harpsong `

and said to him in scorn:

'I do not need a magic

to make you always mourn.

"'I send you home with nothing except your memory of moonlight,

Outling music, night breezes, dew and me.

"'And that will run behind you, a shadow on the sun, and that will lie

beside you when every clay is done.

"'In work and play and friendship your grief will strike you dumb for

thinking what you are-and-what you might have become.

"'Your dull and foolish woman treat kindly as you can. Go home now,

ranger Arvid, set free to be a man!'

"In flickering and laughter

' the Outling folk were gone.

He stood alone by moonlight

and wept until the dawn.

The dance weaves under the firethorn."

She laid the lyre aside. A wind rustled leaves. After a long quietness

Sherrinford said, "And tales of this kind are part of everyone's life in

the outway?"

"Well, you could put it thus," Barbro replied. "Though they're not all

full of supernatural doings. Some are about love or heroism.

Traditional themes."

"I don't think your particular tradition has arisen of itself." His tone

was bleak. "In fact, I think many of your songs and stories were not

composed by human beings."

He snapped his lips shut and would say no more on the subject. They

went early to bed.

Hours later, an alarm roused them.

The buzzing was soft, but it brought them instantly alert. They slept

in gripsuits, to be prepared for emergencies. Sky-glow lit them through

the canopy. Sherrinford swung out of his bunk, slipped shoes on feet

and clipped gun holster to belt. "Stay inside," he commanded.

"What's here?" Her pulse thuttered.

He squinted at the dials of his instruments and checked them against

the luminous telltale on his wrist. "Three animals," he counted. "Not

wild ones happening by. A large one, homeothermic, to judge from the

infrared, holding still a short ways off. Another . . . hm, low

temperature, diffuse and unstable emission, as if it were more like a . . .

a swarm of cells coordinated somehow . . . pheromonally?. . .

hovering, also at a distance. But the third's practically next to us,

moving around in the brush; and that pattern looks human."

She saw him quiver with eagerness, no longer seeming a professor. "I'm

going to try to make a capture," he said. "When we have a subject for

interrogation-Stand ready to

let me back in again fast. But don't risk

yourself, whatever happens. And keep this cocked." He handed her a

loaded big-game rifle.

His tall frame poised by the door, opened it a crack. Air blew in, cool,

damp, full of fragrances and murmurings. The moon Oliver was now

also aloft, the radiance of both unreally brilliant, and the aurora

seethed in whiteness and ice-blue.

Sherrinford peered afresh at his telltale. It must indicate the directions

of the watchers, among those dappled leaves. Abruptly he sprang out.

He sprinted past the ashes of the campfire and vanished under trees.

Barbro's hand strained on the butt of her weapon.

Racket exploded. Two in combat burst onto the meadow. Sherrinford

had clapped a grip on a smaller human figure. She could make out by

streaming silver and rainbow flicker that the other was nude, male,

long-haired, lithe and young. He fought demoniacally, seeking to use

teeth and feet and raking nails, and meanwhile he ululated like a satan.

The identification shot through her: A changeling, stolen in babyhood

and raised by the Old Folk. This creature was what they would make

Jimmy into.

"Ha!" Sherrinford forced his opponent around and drove stiffened

fingers into the solar plexus. The boy gasped and sagged. Sherrinford

manhandled him toward the car.

Out from the woods came a giant. It might itself have been a tree,

black and rugose, bearing four great gnarly boughs; but earth

quivered and boomed beneath its leg-roots, and its hoarse bellowing

filled sky and skulls.

Barbro shrieked. Sherrinford whirled. He yanked out his pistol,

fired and fired, flat whipcracks through the half light. His free arm

kept a lock on the youth. The troll shape lurched under those

blows. It recovered and came on, more slowly, more carefully,

circling around to cut him off from the bus. He couldn't move fast

enough to evade it unless he released his prisoner-who was his sole

possible guide to Jimmy

Barbro leaped forth. "Don't!" Sherrinford shouted. "For God's sake,

stay inside!" The monster rumbled and made snatching motions at

her. She pulled the trigger. Recoil slammed her in the shoulder. The

colossus rocked and fell. Somehow it got its feet back and lumbered

toward her. She retreated. Again she shot, and again. The creature

snarled. Blood began to drip from it and gleam oilily amidst

dewdrops. It turned and went off, breaking branches, into the

darkness that laired beneath the woods.

"Get to shelter!" Sherrinford yelled. "You're out of the jammer

field!"

A mistiness drifted by overhead. She barely glimpsed it before she

saw the new shape at the meadow edge. "Jimmy!" tore from her.

"Mother." He held out his arms. Moonlight coursed in his tears.

She dropped her weapon and ran to him.

Sherrinford plunged in pursuit. Jimmy flitted away into the brush.

Barbro crashed after, through clawing twigs. Then she was seized

and borne away.

Standing over his captive, Sherrinford strengthened the fluoro

output until vision of the wilderness was blocked off from within

the bus. The boy squirmed beneath that colorless glare.

"You are going to talk," the man said. Despite the haggardness in his

features, he spoke quietly.

The boy glared through tangled locks. A bruise was purpling on his

jaw. He'd almost recovered ability to flee while Sherrinford chased

and lost the woman. Returning, the detective had barely caught him.

Time was lacking to be gentle, when Outling reinforcements might

arrive at any moment. Sherrinford had knocked him out and dragged

him inside. He sat lashed into a swivel seat.

He spat. "Talk to you, man-clod?" But sweat stood on his skin, and

his eyes flickered unceasingly around the metal which caged him.

"Give me a name to call you by."

"And have you work a spell on me?"

"Mine's Eric. If you don't give me another choice, I'll have to call

you . . . m-m-m . . . Wuddikins."

"What?" However eldritch, the bound one remained a human

adolescent. "Mistherd, then." The lilting accent of his English

somehow emphasized its sullenness. "That's not the sound, only

what it means. Anyway, it's my spoken name, naught else."

"Ah, you keep a secret name you consider to be real?"

"She does. I don't know myself what it is. She knows the real names

of everybody."

Sherrinford raised his brows. "She?"

"Who reigns. May she forgive me, I can't make the reverent sign

when my arms are tied. Some invaders call her the Queen of Air and

Darkness."

"So." Sherrinford got pipe and tobacco. He let silence wax while he

started the fire. At length he said:

"I'll confess the Old Folk took me by surprise. I didn't expect so

formidable a member of your gang. Everything I could learn had

seemed to show they work on my race-and yours, lad-by stealth,

trickery and illusion."

Mistherd jerked a truculent nod. "She created the first nicors not

long ago. Don't think she has naught but dazzlements at her beck."

"I don't. However, a steel jacketed bullet works pretty well too,

doesn't it?"

Sherrinford talked on, softly, mostly to himself: "I do still believe the,

ah,

nicors-all your half-humanlike breeds-are intended in the main to be seen,

not used. The power of projecting mirages must surely be quite limited in

range and scope as well as in the number of individuals who possess it.

Otherwise she wouldn't have needed to work as slowly and craftily as she

has. Even outside our mind-shield, Barbro-my companion-could have

resisted, could have remained aware that whatever she saw was unreal . . .

if

she'd been less shaken, less frantic, less driven by need."

Sherrinford wreathed his head in smoke. "Never mind what I experienced,"

he said. "It couldn't have been the same as for her. I think the command

was simply given us, 'You will see what you most desire in the world,

running away from you into the forest.' Of course, she didn't travel many

meters before the nicor waylaid her. I'd no hope of trailing them; I'm no

Arctican woodsman, and besides, it'd have been too easy to ambush me. I

came back to you." Grimly: "You're my link to your overlady."

"You think I'll guide you to Starhaven or Carheddin? Try making me, clod-

man."

"I want to bargain."

"I s'pect you intend more'n that." Mistherd's answer held surprising

shrewdness. "What'll you tell after you come home?"

"Yes, that does pose a problem, doesn't it? Barbro Cullen and I are not

terrified outwayers. We're of the city. We brought recording instruments.

We'd be the first of our kind to report an encounter with the Old Folk, and

that report would be detailed and plausible. It would produce action."

"So you see I'm not afraid to die," Mistherd declared, though his lips

trembled a bit. "If I let you come in and do your man-things to my people,

I'd have naught left worth living for."

"Have no immediate fears," Sherrinford said. "You're merel

y bait." He sat

down and regarded the boy through a visor of calm. (Within, it wept in him:

Barbro, Barbro!) "Consider. Your Queen can't very well let me go back,

bringing my prisoner and telling about hers. She has to stop that somehow. I

could try fighting my

way through-this car is better armed than you know-but that wouldn't free

anybody. Instead, I'm staying put. New forces of hers will get here as

fast as they can. I assume they won't blindly throw themselves against a

machine gun, a howitzer, a fulgurator. They'll parley first, whether their

intentions are honest or not. Thus I make the contact I'm after."

"What d' you plan?" The mumble held anguish.

"First, this, as a sort of invitation." Sherrinford reached out to flick a

switch. "There. I've lowered my shield against mind-reading and shape-

casting. I daresay the leaders, at least, will be able to sense that it's

gone.

That should give them confidence."

"And next?"

"Next we wait. Would you like something to eat or drink'?"

During the time which followed, Sherrinford tried to jolly Mistherd along,

find out something of his life. What answers he got were curt. He dimmed

the interior lights and settled down to peer outward. That was a long few

hours.

They ended at a shout of gladness, half a sob, from the boy. Out

Queen Of Air & Darkness

Queen Of Air & Darkness A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows Operation Chaos

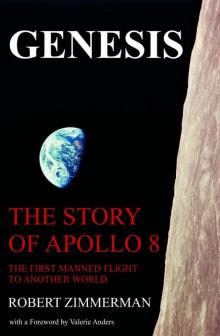

Operation Chaos Genesis

Genesis